Centralville Files – 9-22-2017

The part of Lowell that I. personally, knew best extended along the Merrimack River from the Bridge Street bridge – corner of Bridge St. and Lakeview Avenue – to Collinsville in Dracut, all along the very long Lakeiew Avenue, and upwards toward Upper Centralville near the Lowell/Dracut line. This chunk of rough, granite-laden territory, which was dotted with occasional maple, chestnut and elm trees plus scrubs, stood out in the eyes of passing visitors as proof-positive of a once more prosperous past.

Urban renewal might have been on the minds of wishful residents, but the coffers at City Hall appeared to be as sparse as Mother Hubbard’s pantry.

Note to the reader: The romantic travails that Henry VIII faced in England in 1550, which prompted the creation of this lampooning, nursery rhyme, have very little to do with the anxieties found in Lowell during the Great Depression, but this poem is included here as a historical touchstone reminding us all that troubles and woes in the affairs of love/lust and in getting sustenance have always marked our daily lives. Kings and paupers all suffer the so-called slings and arrows of Mother Nature’s apparent fickleness. “Why is life so difficult?”

Happily, for me, this land was also adorned with the major, social crossroads of my youth that included locally famous thoroughfares carrying the names of West Sixth, Hildreth , Bridge, Cumberland and Lakeview, which ran, more or less, parallel to the river’s shoreline. Streets running in a north-south direction, in contrast, were named: Ennell, Lilley, Ludlam, Farmland and Aiken. Loosely speaking, our Lower Centralville habitat represented an almost Cartesian grid of happy symmetry where peace and well being generally filled the air. Some discontent might be expressed by less indulgent individuals, of course, but not very often.

Interspersed in this real-estate tapestry, there were several, small, interconnected, mostly residential neighborhoods (city blocks) where the blue-collar, working-class families resided either in the ubiquitous, multi-story, multi-family, clapboard tenements or in individual single or two family homes.

Aiken Street ran into the residential nexus of Lower Centralville and also provided the residents in the area with an easy access – across the Aiken Street Bridge – to the busy patchwork of retail/residential buildings – hobby shops, tenement blocks, pharmacies, fish stores, a movie theater, variety stores, malt shops, etc. – found in that so-called portion of the city, the Acre. (more on the Acre and Little Canada, later). Last but not least, there stood at the corner of Aiken and Merrimack Streets a most impressive, post-Gothic edifice of rough granite and French spiritual grandeur, the Saint-Jean Baptiste Church.

Since Aiken dead- ended at Merrimack Street, the traveler, usually a passenger on the bus, then only needed to turn left to soon find himself/herself crossing Dutton Street at City Hall and approaching several large department stores and, finally, Kearney Square, the historic center of town.

The Franco-American Nexus of Lower Centralvile

Given that the inhabitants of my family’s immediate neighborhood maintained a strong allegiance to their Roman Catholic ancestry going back, at least, to the Quebec Act (1775), it is not surprising to expect that the Ecole Saint-Louis de France (elementary school) and the associated Eglise Saint-Louis (church) played an important and formative role in the daily lives of its parishioners. These followers occupied a residential area, which was several blocks in size that contained a light scattering of retail stores. These places of business were distributed across a rectangular piece – trapezoidal might be a better description – of land that, generally speaking, tilted upwards and away from the river’s edge, AKA Lakeview Avenue.

Most of the people living within this patchwork – many of them had spent their early years growing up in small Quebec towns and villages – had little need to travel any more than a few miles from their homes.

This is territory where my experience as a local daily news-paperboy for the Lowell Sun was tested, again and again. Local Franco-Americans were not known for their insouciance with regards to the prompt delivery of their favorite news source even when their newsboy – there were some news girls, also – was barely dealing with ice, sleet and rain from a second snowstorm, a true Nor’easter, in the past two days, which precipitated a record number of school closings all over the city, and practically crippled the use of city maintenance vehicles.

There probably was a valuable lesson for a young entrepreneur to firmly understand from this harsh behavior. There is no crying permitted in the life of a dedicated messenger of truth, justice and the American way. Note that the average mail-carrier (le postillon) was treated with more respect and appreciation than the intrepid and entrepreneurial youngster of either gender bringing the news of the world to every doorstep.

Tiny Geographical Details

As a rough description (Note: official land surveyors might grimace painfully while grasping their advanced, laser-optical tripods in reading the following), this territory extended along West Sixth Street from Bridge Street to Farmland Road and beyond in one direction toward Dracut, and, in a northward fashion, to Hildreth Street where Hildreth crosses into xxx at Hovey Square.

More on the Flavor of our Extended Neighborhood

Sometimes, the one or two-family private dwellings also provided year-long, room-and-board living arrangements for needy, day-laborers in the textile mills. Very often though, any spare room in private homes was set aside to provide a home for a nearly-destitute or ailing relative. Grandparents could, sometimes, spend their ailing years as a nurtured member of a young, growing family where charity at home was still a valued, Canuck family trait.

Many quaint, Quebec-like stories, which we heard at school, reminded us of the difficult. economic situations faced by many aunts, uncles and grandparents that were too frail and weak to still earn their own bread. The concept of early retirement apparently had very little meaning during the “golden years” of such, unfortunate, family members.

The Good Works of Religious Societies

The idea of giving alms to the poor and to offer succor to the less fortunate among us rings true in the hearts and minds of the Christian protagonists, and reverberated in small towns and villages throughout Western Europe going back to the Gospels – the Good Samaritan stands out as an example – and, much later, to the days of the Renaissance.

Since most people with whom we interacted regularly in our neighborhood were of very modest means, “faire la charité” – “to do charitable acts” – underscored the essential feature of being a good, Franco-American citizen in a mostly English speaking environment. Of course, we were all encouraged to be fair, honest and dependable when dealing with others – all others – but being “charitable” went beyond the basics.

Often, my mother would invite a door-to-door salesman to come inside the kitchen to enjoy a piece of freshly baked pie – cinnamon apple and lemon meringue were favorites – and to chat over a cup of tea made in the English fashion. This was simply being hospitable. But in more serious situation, a relative might stay the night or a recently orphaned child – usually, an acquaintance of the family – might be invited to stay for weeks or months.

World War Two, WWII, Displaced Persons known as DPs

When my parents in 1948, took in Madame Fortin, a displaced Belgian woman, and her young son (his name escapes me), to live with us for weeks on end, she was expressing “la charité” in its most fundamental form, i.e., to take in the stranger to live with you.

It might be important to note that in 1948, my father was barely earning enough wages at three jobs to support my mother, himself and three young children – Denise was born in 1950.

Doing charitable works when you are financially strong is most admirable, but helping others in need when you, yourself, are barely surviving through the harsh realities of daily life is quite another matter.

On this very issue, I overheard my Mom and Dad expressing differences of opinions regarding acts of kindness. She had met Madame Fortin, months before, at the large, heated and pleasant Kearney Square waiting room that the bus company provided for its customers as they awaited the arrival of the next bus going in their direction.

Since my mother was an affable person eager to exchange pleasantries with anyone that she found interesting, her meeting Madame Fortin was completely fortuitous. Maybe, the Fates would have it so?

In sharp contrast to this state of gentle affability, which characterized my mother, my father embraced a distinctly more apprehensive, if not severe, attitude toward strangers. Such might be called a New England reservation when dealing with others whom you do not know. An open display of tentative affection toward a stranger in public represented behavior outside the Lowell norm, at least, for my father.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

The

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society_of_Saint_Vincent_de_Paul

The charitable organization founded in France in 1833 for the care and upkeep of the poor, which was called the Society of Saint-Vincent de Paul, represented for us a potential safety net in the event that my Dad no longer could continue working his 55 to 60 hours per week. Naturally, my parents dearly hoped that these hidden reserves – or imagined reserves – never would be needed to save our sinking family ship of state. In this case, however, their optimism proved to be a slightly foolish wish.

After my Dad died in early January of 1953, my mother sent out a rather frantic SOS signal that was picked up by my attentive Uncle Lucien, a recently retired U.S. Army Colonel and a West Point graduate. All other relatives were either too poor or busy with their own lives to offer assistance.

However, this emotional wake up call proved strong enough in the hearts and minds of a few neighbors that it generated a rather unique plan to possibly save our bacon and, hopefully, provide my mother and her brood of four young children an escape from the present reality. More on this fantastic plan will appear in a later section.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

Later, similar WWII stories about many DPs, displaced persons, who were barely surviving in bombed out factories, empty barns and on fractured streets in Holland, France, Hungary, Germany, Poland and elsewhere made more sense to us in a shared poignant moment. It seems that certain human experiences only trigger a deep emotional connection shared by others when these others have also smelt, seen and heard similar experiences. It remains a visceral, gut reaction – rational at all.

No simple written text can adequately convey fear, nausea, loss and angst. So, in many ways, the immediate post-war years felt by many in Lower Centralville were highlighted by reveries, reflections, xxx and vague aspirations for a new, safer and more fulfilling life to come.

Our large, shortwave, RCA radio still dominated a special corner of our Ludlam Street kitchen, next to the white, upright icebox (refrigerators were too expensive) and that pedal-operated, Singer sewing- machine, which had graced many a kitchen over the years.

Add more on the old wood-burning stove , family dinner table, etc.

These were hard times for many, low-skill, unemployed, Lowell, former wage earners.

Happier times might have existed decades before the Big Crash on Wall Street, but the sagas of the “good old days” that reached my tender ears in the 1940s and 1950s spoke mostly of ignorance, shabby living conditions, poor nutrition and psychic loneliness in an empty, moribund town. Could beer and whiskey be the easy solution?

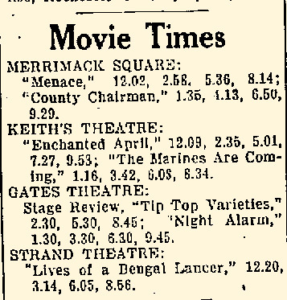

There were, however, several movie theaters and an opera-house in operation

years before the start of World War II so the walking wounded from 1929 to the end of 1941 could be entertained cheaply with magic doses found in Hollywood’s comedies, gangster films and cowboy sagas.

Of course, the big band sounds of xx and vvv mixed in with readily available booze, the contraband of the era, helped to lighten the financial load felt by everyone plus his/her dog. The American author and journalist, Studs Terkel, from Chicago would have felt welcome and completely at home in Little Canada, the Acre, the Highlands and , also, at the Bon Marche department store on Merrimack Street..

If there were “happy pills” available to all, speak-easy dives, movie houses and dance halls were their bountiful sources. Of course, the more religious folks could always find emotional solace in the city’s many churches and a Jewish temple. Perhaps, these “hard times” were a bit easier to live through for the devout persons with a deep grounding in the tales of woe expressed in both the Old and New Testaments?

“What had happened to the industrial dynamo of New England textile factories? When might it all turn around for the underdogs and the industrialists of this world?”

Or, as my Aunt Lida of Ouellette’s Lunch at the corner of Moody and Austin was often heard to say, “When will my ship come into port?”

in addition to local streets Aiken, Ennell, Lilly, Ludlam

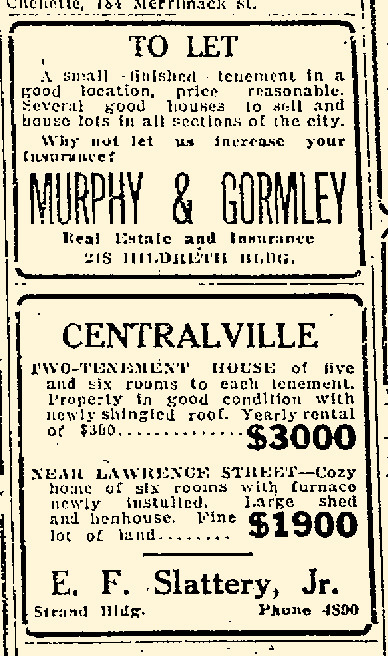

#1 It looks like a great deal for a successful businessman in the charming ambience of Centalville, Lowell’s hotbed for civilized living outside the dirt, grime and noise of the inner, industrial city.

Mr. Slattery, Jr. is offering this neat, six-room residence in an up-scale, suburban neighborhood located just across the Merrimack River. For anyone, who loves chickens and light farming adventures, the gracious Mr. Slattery has included a newly installed furnace plus a fancy hen house to the deal.  Note that environs around Lawrence Street is nothing to sneeze at when urban sophistication is discussed at your country club dinners.

Note that environs around Lawrence Street is nothing to sneeze at when urban sophistication is discussed at your country club dinners.

But, if you wish to create a long-term cash-cow for you and your Mrs. in the years to come, please look into the multi-family rental unit also listed in the ad. This is, certainly, one that wets the appetite of any successful, young entrepreneur, who is eager to get out of the day-to-day grime of Spindle City’s 60-hour workweek on Appleton Street.

Don’t delay for another minute. This is the year of 1900 AD and Lowell’s future economic success is, yet, to reach its peak. There is gold in those thriving sweatshops!

Contact Mr. Slattery immediately at 4800 and remember that he has a fancy office in the Strand Bldg where only the success-minded feel welcome.

#2 School Sites – 11-8-1902 or Where to put the Greenhalge School?

The bustling locale of Lower Centralville has gotten the attention of the Lowell School Board since new classroom facilities would soon require a convenient, new school building with easy access from houses located on existing streets (some still needed sidewalks) such as Ludlam, Lilley, Ennell, West 6th, Cumberland, Aiken, etc.

These were the weighty decisions now facing Lowell as it entered its first 100 years as a textile manufacturing superstar with an international reputation. But, centers of industry need educational and training establishments to nurture the minds of children with parents employed in the mills.

The Hovey Square site at the end of Aiken Street was first considered, but since it was located almost at the Dracut line, this possibility was quietly set aside.

Curiously, though, a large,vacant site owned by Mr. Jacques Boisvert (a well-known and successful contractor and land developer), which was located at the corner of Ludlam and Dana had been offered to the city for a mere ten cents a (square) foot. However, that asking price seemed a bit too steep in the minds of the dutiful city fathers and mothers, who, probably, harbored a deep-seated, hard-nose, New England attitude about thrift. That deal had fallen down like a straw-man in the New Hampshire winds.

NOTE:

As an interesting aside to this article, the author quietly remains thankful, even today, that the Ludlam-Dana deal did fall through since that piece of land happens to be the location of the Victorian-style house that his family eventually rented from the mid-1940s to 1962. It seems that Mother nature insists upon amusing us, its children, again and again.

Fortunately, though, the city’s efforts stumbled upon an alternate possibility. The Lawrence Manufacturing Company, a major employer in the city, owned a large chunk of land on Ennell Street, which was offered at only four cents a foot.

Apparently, there had been some discord over this possible choice, but the wheels of municipal decision-making eventually reached some agreement. But, if accepted, Cumberland Road would need to be extended beyond its present location.

However, everything considered, this choice was deemed quite desirable as a solution to the board’s requirements. Progress filled the air. Lower Centralville gained new respectability.

#3 Ward 6th Precinct Politicians – 9-1-1908

Everyone loved municipal elections, back then, or so it seemed. Democratic fervor of the two-party variety bustled all over the city. Even, Lower Centralville got into the act.

On the Republican side of the ledger, fine candidates for deputies and inspectors came forth from streets carrying names like: Lilley, Aiken, Beaulieu, Dalton, West 6th and Ludlam. Charles Boisvert, brother of Jacques Boisvert, presented himself as a candidate from 94 Lilley Avenue.

On the Democratic side of the issue, several men – a couple French-Canadian – offered themselves as worthy candidates for positions of deputies and inspectors. Included in this mix were representatives from streets named: Lilley, West, Front, Fulton and Cumberland.

Only Lilley and Cumberland played some important role during the days when my brother and I covered that territory with our paper routes. We knew that landscape like the back of our hands.

In summary, this imperfect and partial study would suggest that municipal leaders emanating from the neighborhood streets of my youth were, usually, of a Republican leaning. Such was, certainly, the case for the Bolduc and Charbonneau adults and children of my youth.

For socio-ethnic reasons centered on the Irish versus Franco-American tensions that originated 80 to 100 years before, the English-speaking Irish men or women of the city had gravitated toward the Yankee-Republican political position favored by mill owners whereas the French-speaking counterparts had adopted the more immigrant-centered position fostered by the Democratic party.

As a result, labor strife in the factories often had political underpinnings that further fueled the fires of discontent between these two groups. All was not sunshine and roses for the largely undereducated, poorly-paid mill worker, who often lived with his/her large family in over-crowded, sub-standard wooden tenements that dotted the city’s several socio-ethnic ghettos.

The Franco-American ghettos of “Little Canada” and the Greek-American ghettos of Lowell’s Acre speak volumes on the daily lives of the immigrants. Of course, other ethnic groups like the people of Polish, Lithuanian and Portuguese extractions also congregated in segregated compact neighborhoods. The first two groups seemed to find shelter in Lower Centralville in the Front Street and Lakeview Avenue corridors by the river, which merge into Bridge Street.

In contrast, the Portuguese had a light industrial/residential neighborhood for themselves along Perry Street near Andover Street. It extended to Shedd Park in one direction and toward Route 38 in another. It had the flavor of Portugal with a Roman Catholic Church in its geometric center. Many a baptism and a matrimonial ceremony took place there as was also the case for funeral services.

In many ways, growing up in Lowell in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s meant being surrounded by an interesting panoply of cultural, ethnic, linguistic, religious and socio-economic forces that end up shaping one’s personal reality or world-view. There was much to absorb and to understand, at least, partially.

#4 Tenement house – 12-17-1910

A three tenement house made of cement (not 2 by 4 studs, mind you) was to be started on Dalton Street in the coming spring with Mr. Noel Houle in charge of construction. Mr. Houle’s credentials remained unspecified but, apparently, his expertise was so well-known that no explanation seemed necessary to the reader.

This all-new construction approach would include the latest improvements in modern living such as hot water tanks, bathtubs and set tubs. Plus, the bathroom floors would be made of cement – quite unusual for sure.

The concept of a set tub might have been new to the average Centralville homeowner or renter, but the fact that it was mentioned as a great new feature was meant to highlight the desirability of such a home improvement.

Note that a housewife’s duties in the early part of the 20th century would, naturally, also include doing the weekly family wash somewhere on the kitchen floor or, perhaps, outdoors in pleasant weather.

Often, the dirty clothes were placed into a large, movable, metallic bathtub and a commercial detergent was added to the mix. Finally, the whole xx was quickly drenched with a pailful of hot water from the kitchen stove. At that point, the tired housekeeper was expected to be a human xx, similar to the modern washer machine. Mixing that xx by hand XXXXXXXXXXXXX

Set tub: A deep wide sink or tub, usually of porcelain, slate, or soapstone; used for washing clothes, etc. – See: Free Dictionary on the web.

(yes, in earlier days, one was expected to bathe in this container)

The Jacques Boisvert Phenomena

In 1910, it was hardly possible to come across a Lowell Sun newspaper article on land development, street repairs and tenement construction to not stumble upon the name of Jacques Boisvert, the man who was putting up houses and new tenements in Centralville faster than any of the competition.

The guy – he turned out to be a distant relative – even had a low down payment arrangement with his buyers where they would assume full ownership of a building after years of fixed monthly payments to his company. How he financed this mortgage arrangement through a local bank remains mysterious, but clearly

his financial expertise seemed to play well with his architectural flair.

According to the article. Mr. Boisvert has build almost all the houses on Boisvert, Beaulieu, Jacques, Campaw and the upper part of Hildreth and Essex. If, as a buyer, you were interested in getting yourself a new house on streets like: Cumberland, Farmland, Fisher plus the the six mentioned above, then, Mr. Boisvert just might be the man to see.

Simply being a fine craftsman as an independent contractor may not have been sufficient for success in 1910. The nuts and bolts of financing a sale could make or break a transaction. This remained one of Jacques Boisvert’s strong points.

Apparently, there was more to success in the construction business than simply building a fine structure.

Although the output of the textile mills in the city and in New England, in general, had been showing signs of economic slowdown, even decline, since the last decade of the previous century, local business owners in the trades (carpentry, plumbing, etc.) still sought to find a passive source of income by renting three XXX and four family tenements to mill employees.

Often, these structures were constructed, specifically, for that purpose. Owning and renting tenements in neighborhoods with ready walking or bus access to the several mills still in operation was a gold mine. Most mill workers earned too little to purchase a house of their own, so rentals were in constant demand.

XXXX house to individuals too stressed out financially to buy a house

XXX there was more to being an outstanding

Other sections of town were similarly buzzing with activity. Another contractor, Mr. Avila Sawyer, was signaled out as a prime mover in Pawtucketville with his construction projects on Moody Street (now, University Blvd) and Mt. Hope Street plus an 11-room cottage for himself on White Street, the prettiest domicile in that part of town.

Residential growth could readily be detected by any passer-by. However, all this new glitz might have been seen as risky by an independent financial analyst, who was familiar with the city’s bond issues.

Esther Wolfe was even putting up a storage shed at 20 and 22 Chelmsford Street, which was to measure 22 by 30 feet, one story only. Clearly, it was a building boom to beat other building booms.

Lowell, Massachusetts was on the march. Nothing could hold it back.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

#5 West Sixth St. Fire-station – 12-23-1910

In December 1910, the frenzy of new building construction in Centralville must have stimulated the city father’s to build a fire-station with adequate incendiary control to merit the title of the West-6th Street Fire-station.

Such a structure was, indeed, erected to hopefully serve those community needs. Its red stone facade with two impressive broad garage door openings plus a tall ( ~ 50 ft) tower housing a strident siren filled our spirits with a belief that fires in our part of the city would quickly yield their destructive spell to the local technology of the day. For me, during the years starting in 1946 and going to 1953 when I attended elementary school, this gigantic monument of grotesque proportions served as a civic reminder that someone, somewhere at City Hall cared about our well-being. It felt good to be protected.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

West Centralville Land development – 11-22-1911 #6

&&&&&&&&&&&&

Cecile Bolduc graduation from St-Louis – 6-23-1916 #7

Immigrants usually face several challenges as they attempt to integrate themselves into the mores and societal norms of their adopted country. Certainly, not speaking the language of their new circumstances presents a hurdle that must be overcome if they are to comfortably fit into the daily activities in their surroundings.

The Ecole Saint-Louis – St-Louis Elementary School – had as one of its primary goals to prepare young, Franco-American students, boys and girls, to read, write and speak a fluent English, which was used throughout the city. Since these children usually lived in self-segregated, and often poor neighborhoods, quite similar to European ghettos, the school’s religious staff focused much of its attention on making English the school language for half of the classes taught every day.

So, as an example, classes in math, science, American history, English composition, civics, etc. would be taught in English during the first half of the day whereas Catholic religioous studies, Quebec history, music, French grammar, composition and dictation, etc, might fill the second half of the day. Students were free to choose their language of discource in the school yard at recess.

The school day ran Monday through Friday from 8:30 AM to 3:00 PM with a 45- minute lunch break when most of the students returned home for their meal. The lunch escapades were run smoothly with lots of discussions shared by all to and from school. For me, it was a program that I followed from kindergarten to the eighth grade, a very meaningful experience.

It is definitely worth mentioning that my brother Bob and two sisters, Michelle and Denise, also benefitted from the dedicated efforts of these nuns, Les Soeurs de l’Assomption de Nicolet, Province de Quebec.

The attached Lowell Sun article dated 6/23/1916 highlights the 8th grade graduation activities held at St-Louis School. Among the students receiving diplomas, that day, was my aunt, Cecile Bolduc, my father’s older sister. Family names like Bernier, Boucher, Champagne, Lemieux, Picard, Chaput and Rancourt sound like old-home week to me.

Childhood impressions stay with you for a lifetime.

&&&&&&&