It seems that I was aware, very early in life, of many economic, educational, linguistic and cultural limitations, which the different ethnic groups within the city all seemed to acknowledge and make an effort to overcome. Immigrants, who were often quite illiterate (poorly educated and trained) on the ways and means of reaching an acceptable degree of economic success constituted the vast majority of people with whom I grew up. But, I usually saw these other strangers through a well-established prism of French Canadian, 1800th century, Catholic lens – a unique historical viewpoint.

However, my world-view at the time, although quite parochial, remained, at least, open to the idea that we were all in this human situation together. Each ethnic group had its own historical perspective with unique ideas, values, hopes and beliefs, which, somehow, could be blended together into a workable, long-term reality for all. Faith in the system of American democracy in which we bathed on a daily basis seemed deep and genuine.

The Lowell Sun newspaper and the open access to the entire world offered by the Lowell City Library certainly encouraged the idea that today’s limitations were not reasons to abandon hope for a better and more fruitful future.

“There might, indeed, be gold in them there hills if only you tried very hard, again and again.”

That glimmer of hope had been a spark that gave poorly educated and destitute immigrants from Greece, Ireland, Poland, Romania, French Quebec Province, Lithuania, Italy, Jewish-Russia and elsewhere the reason to carry on. Although it was tough, maybe, life was worth living after all.

Being the world-recognized center for the American Industrial Revolution in the mid-19th century, the city became a magnet for destitute individuals seeking a better life for themselves and their families. The long hours of harsh labor under conditions that were most advantageous for the fabrication of cotton fabric – 90 degree temperatures in a controlled 90 percent humidity environment – were the work-a-day facts of life for many of the mill workers.

Recessions, Unemployment and Economic Downturns

The national demand for fabric products by industry, government and the general public varied greatly over the decades under conditions that reflected the country’s multifaceted interests at the time. There were times of boom and bust such as periods of The Civil War and World War One, WWI, plus the economic growth periods around electric and steam-powered engines, refrigeration, road building, the manufacturing of aero planes, etc.

Much was happening across the nation in addition to the growth of serious competition in the textile and shoe manufacturing worlds, areas that had long been the mainstay of Lowell’s economic harmony.

Halcyon Days of Economic Spurts and Hellish

Unemployment

Decades before I became aware of the daily travails and disappointments of Lowell mill workers, both textile and shoe manufacturers, my Quebecois grandparents had long before established themselves as low-paid, under-skilled factory laborers cranking out fabrics and/or leather goods for the Boston-based investors and entrepreneurs, the Invisible Hand of Industrial Power. All went quite nicely when the well-balanced management/worker mix provided investors with a healthy return on investment, ROI, but in life there are unexpected twists and turns that can seriously impact the bottom line.

The experiences of early workers in the mid to late 19th century Lowell scene were no different. How does a small family of mother and father with three children, all under the age of five, manage to survive when the landlord has pulled eviction papers on them and the local police is helping family members remove personal belongings from their tenement? Where do the newly homeless go? When does yet another misfortune possibly lead to a mental breakdown or to a suicide?

Analysis of Statistical Data Stored in the Archives of the Lowell Sun

Since I was fortunate in joining my family in distress late during the Big Depression (1939), my personal memories of these hard times remained remarkably benign although I do recall hearing fascinating stories about family members, who made it and others, who bought the farm or simply disappeared.

The general attitude could be summed up clearly as:

“Life is tough. Keep a stiff upper lip. Suck it up.”

Of course, your friends, relatives and, maybe, your neighbors, too, could give you some moral support and emotional encouragement but real help in terms of food, clothing, housing, transportation etc. ?? Well, there was the Saint-Vincent de Paul Society, a Catholic charitable group with 19th century, European origins going back to 1833 and, of course, caring neighbors and relatives, who might still have resources in their cupboards. The pickings were quite skimpy, if not really discouraging. The cornucopia of our life blessings had somehow shriveled down to a sad empty lunch pail.

What to do? What to do? Prayers alone including special Novenas (a standard recourse for my parents and relatives) with a focus on relief from the gloom of joblessness were not sufficient to deal with the bare bones of our pantries.

Personal Project – Attitudes of the Survivors and Victims

For many years since those days after the Roosevelt Depression (~ 1938) and the challenges of WWII, I have often wanted to better understand the feelings and day-to-day responses that my grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, etc. had to the, sometimes, unpleasant truths imposed upon them when they had, perhaps, expected a more sane and benign world.

Secretly, I wanted to be closer to them psychologically and to, maybe, understand them a bit more. This was my attempt at a rapprochement across generations. But, how could I do this?

The answer appeared right before my eyes. A couple of years ago, I became aware of a new digital application called optical character recognition, OCR, which might permit me to read the news printed in old versions of the Lowell Sun. Here was a treasure trove of daily events printed in my local newspaper and available to anyone, who might be interested in family history, ancient sports events, WWI and WWII military phenomena. I had found a valuable touchstone – a minor Rosetta Stone in a sense – to the recorded events of yesteryear.

Number of Suicides recorded by Lowell Sun vs. Date

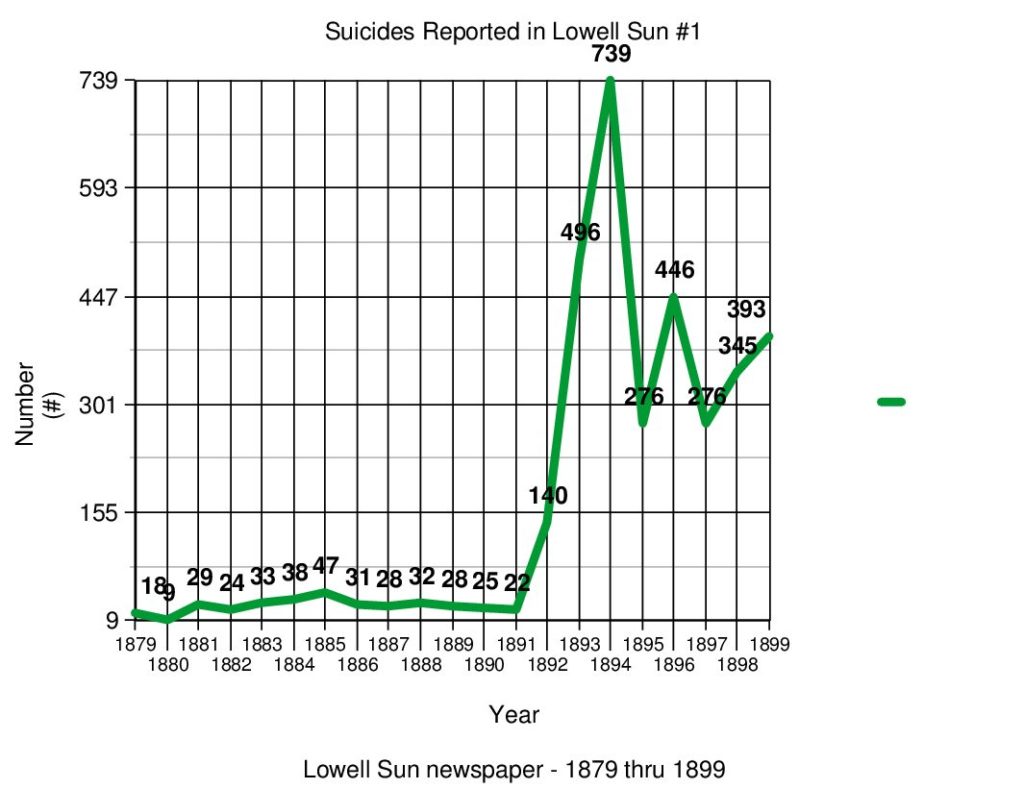

Early statistics going back to the start of Lowell’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse (~1835) are not readily available, but the Lowell Sun can provide the interested reader with data going back to 1879. The following graph shows the number of reported suicides versus the date from 1879 to 1899. This was still a time of ramping up production whilst economic downturns and worldwide recessions hampered the economy.

The yearly suicide rate recorded by the Lowell Sun newspaper for the period between 1879 and 1891 ranged from 9 to 47 cases, but in the subsequent years from 1892 through 1899, these rates had suddenly jumped to a peak of 739 with later fluctuations in the range of 446 to 278 cases per year. Any newly-arrived immigrant must have been generally aware of the tentative nature of his/her future.

These were disturbing statistics. Clearly, the daily lives of the city’s population had shifted greatly in a negative fashion during the last decade of the century. Why were there so many more people choosing to end their lives in the hot bed of the American textile bonanza?

Ancient Quebec Relatives set up Shop in New England

The outflow of poor, frightened, disgruntled farmers from Quebec Province was in full stride in the 1850s through the 1860s time frame. It was precisely during these two decades that many of my family connections to the old country were first established. However, the initial trickle of French-Canadian immigration after the Civil War became a veritable flood of job seekers in New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island where the textile manufacturers were setting up red-brick, industrial buildings, four to five stories in height, each covering a city block or more in spatial dimension.

The era of mass industrial manufacturing based on the successful integration of hundreds of small, individual sub-procedures, which were under the control of a replaceable operative (a low-skilled worker). No single worker in this production-line operation ever needed to master anything more than the rapid eye-hand, repetitious coordination needed for the successful operation of his/her sub-assembly. All operatives were effectively made replaceable through a clever and efficient division of labor within the plant. Only floor supervisors and company managers had an overall understanding of the operation.

The 1900 through 1929 Time Frame

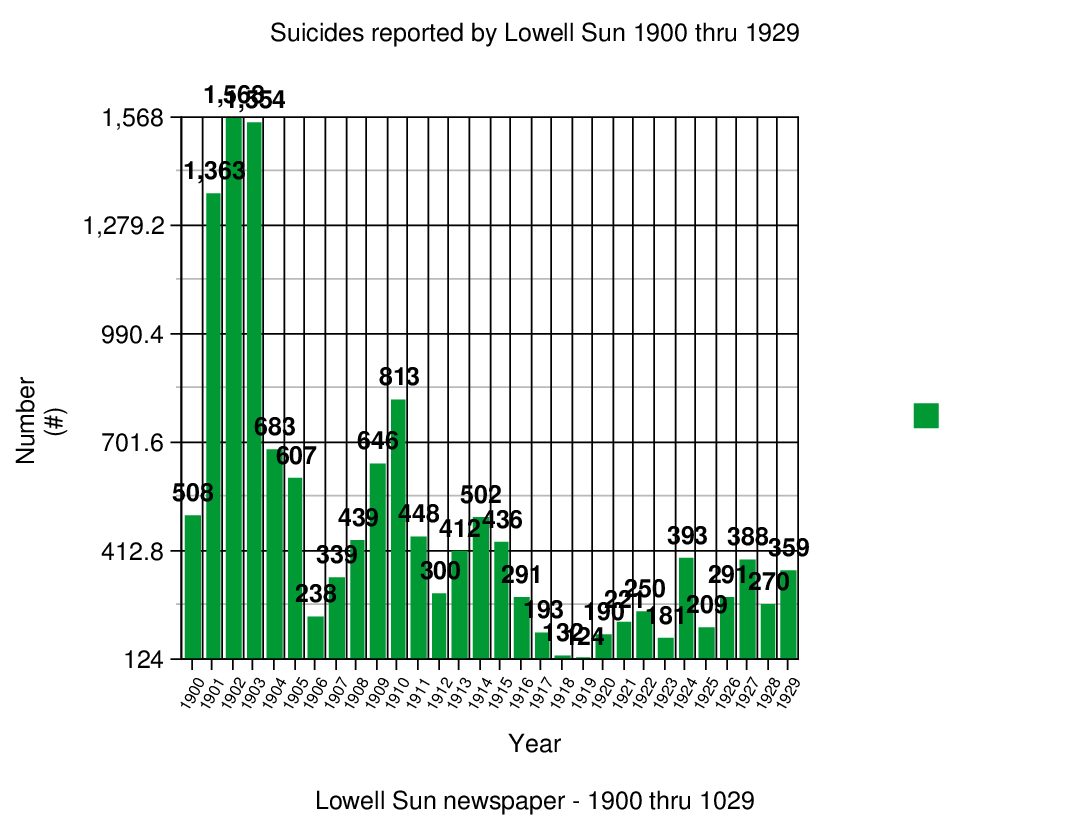

Immigrants flooding into Lowell’s portals in search of temporary lodgings, food, clothing and, perhaps, familiar social and cultural settings needed to quickly find a reliable source of income to kick start their new life in the big city. Lowell had about 100,000 people at the start of the 20th century. Those individuals, who had relatives already established within the community could fall back on this family relationship as a starting point to their exciting future. However, coming into town without a red cent in one’s pocket and knowing nobody must have seemed like an impossible task. Maybe, these individuals did not survive? The economic uncertainty due to world-wide recessional forces in the early part of the 1900s must have seemed like a tough and discouraging additional challenge for the job seekers, strangers really, to overcome. How much stress can a person handle and not fall into alcoholism, gambling and petty thievery? When does it happen that such a person becomes dysfunctional and extremely depressed? No easy answers come forth to address such issues, but the following data flowing from the Lowell Sun’s archives might shed some light on these questions.

Lowell Sun Stats on Suicide Reports from

1900 through 1929, the year of the Crash

After the New England farm girls had left their posts in Lowell’s textile industrial capitalism some years after the Civil War, Irish and Franco-Canadian immigrants (les Canucks) rushed in to replace them. Perhaps, distressed workers from Greece, Poland, Lithuania, etc. also arrived during that period. I do not know.

According to the statistical data given above, during 1901 through 1903, the annual rate of reported suicides ranged from 1363 to a peak of 1568 self-deaths (suicides) or an average of 26.2 to 30.1 per week, a real horror show.

These must have been extremely difficult times for all my Franco-American aunts, uncles and grandparents since many of them had first set foot on American soil during that period. Others, including the Charbonneau, Boisvert and Clermont relatives, had arrived during the last two decades of the previous century.

Looking back today, I, as a child of the late 1930s, had no idea whatsoever about the day-to-day concerns and worries that might have lead to sleepless nights for these folks. Again, I am reminded that those people around us everyday often have lead lives of remarkable and, sometimes, frightful dimensions and, yet, we know nothing about them on a deeper level.

The only whiff of hope depicted in the otherwise grim numbers presented in the last graph is one, which serves as the economic highlight of Lowell’s early years of the 20th century. The reader is invited to focus his/her attention on the suicide rates for 1918 and 1919, the period of time when our country fought in World War I. One might be tempted to conclude that our military actions with allies on the European Western Front reduced the recorded annual suicide rate to a mere fraction it had reached just years before. As an example, there were only 132 and 124 reported suicides respectively in 1918 and 1919 whereas the previous four years (1914 through 1917) yielded a sad set of larger numbers, i.e., 502, 436, 291 and 193 deaths.

Apparently, the government contracts created for the production of Army and Navy troop supplies such as textile material for uniforms and bedding, tents and also shoes and boots (recall that Lowell was also at the time a powerhouse in the fabrication of leather products) had brought to the city new hope for the many hundreds of factory workers whose bread and butter well-being depended on available work in the factories. In this curious sense, WWI was a blessing in disguise for the many mill rats trying to barely survive in the city. Life has many unexpected twists and turns that continue to challenge us every day. How do you prepare for the unexpected?

The Big Depression followed by WWII – Tough Times

The years following the complete collapse of our country’s economic well-being, which resulted in the painful, social unrest of the 1930s, marked the folly of the then existing investment banking system (the nearly unlimited leveraging on the purchase of stocks and securities), which resulted in the big Wall Street Crash on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. The national, financial house of cards was shown to be but a fiscal Ponzi scene constructed on non-existent capital or assets. Investors scurried, bankers worried and the working poor were soon left with many, many empty lunch pails. Panic was the word of the day!

Lowell’s General Misery Index reported

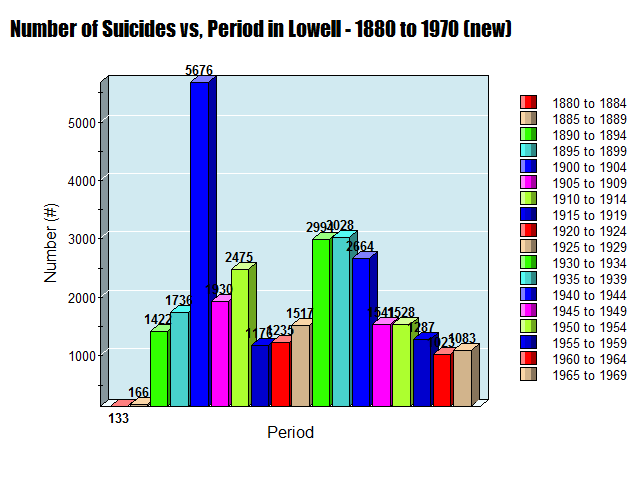

by Lowell Sun from 1880 thru 1969 in Five Year Intervals

Surprisingly, the time period of maximum social distress and despair measured by the city’s suicide rate happened from 1900 thru 1904 (See fifth column in deep blue starting at the left) when 5676 persons (newly arrived immigrants, I suppose) chose to end their lives abruptly through suicide. In contrast, the self-death indices measured during the Great Depression (1930 thru 1939) reached only about 53% of that peak during the five-year period starting in 1930, which was then followed by another five-year stint with equally dismal prospects.

When the economy tanked in 1929, there was little to no rebound in the city’s economic system to make the daily lives of first and second generation immigrants and the factory owners satisfying again. Technology’s powerful grinding wheels had worn out, and it was during this desperate period when my parents plus aunts and uncles were trying to make a go of it in their work lives.

Critical Data related to Lowell’s Socioeconomic Status

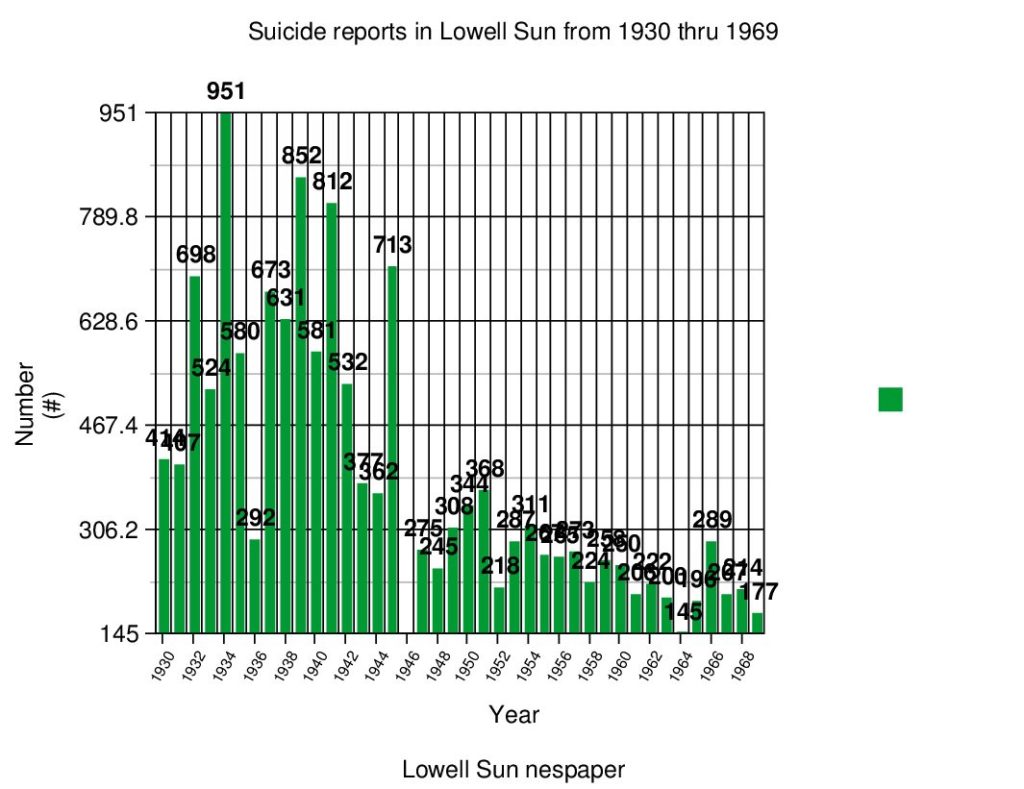

The socioeconomic conditions, which presided in my hometown during the Depression and the years of World War II, fashioned for my relatives and neighbors in the city’s French-speaking communities a rather grim and nasty appreciation of their day-to-day lives caught in many interwoven, cultural and educational limitations. The graph below outlines the measure of contentment experienced by many Lowellites in the period between 1930 and 1969. Generally speaking, these stats helped me to understand a little some of the negativity and modest despair heard in the voices of my townspeople of all ethnic sources during my growing up years.

The year 1934 marked the highest level of suicides reported by the Lowell Sun during the Depression. This marked the beginning of Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation. People were really hurting and national government began to assist citizen’s in maximum distress. Social Security benefits and Aid to Dependent Children programs were first introduced into legislation at that time. Within about two years in 1936, the dismal conditions of despair seemed to have abated to a mere 292 suicide mentions compared to 951, two years before. Slowly, progress could be measured in saved human lives and a glimmer of hope.

Note: The reader is invited to examine the results for the years of 1945 and 1946. During the last year of WWII, there was a spike in the reported suicide mentions of the local newspaper. There were 713 reported cases in 1945 compared to only 362 cases in 1944 or a 97% increase over those two tears. The anxieties of the war in Europe and in the Pacific had worn some nervous systems to the breaking point.

Also in passing, the reader is encouraged to examine the results for 1946 when the Truman administration began to function. No reliable suicide related data could be culled for that year since the Lowell Sun’s database only contains information from January through early March of that year. This type of “memory gap” in related data can really set back the amateur researcher. For that year, therefore, I recorded no information.

Finally, the last bar chart given below is presented to give the reader an overall snapshot view of Lowell’s psychological status over the years. The peak values in the 1980s would merit further investigation, but that inquiry would lie outside the purview of this article.